–

武當劍法大要

ESSENTIALS OF THE WUDANG SWORD ART

黃元秀

by Huang Yuanxiu

[published by 商務印書館 The Commercial Press, LTD, Shanghai, July, 1931]

[translation by Paul Brennan, June, 2014]

–

練剣之要身如遊龍切忌停滯習之日久身與剣合剣與神合於無剣處處處皆剣能知此義則近道矣

右廣川李景林題

The key in sword practice is that your body moves like a swimming dragon, never coming to a halt. After practicing over a long period, your body will unite with your sword, then your sword will merge with your spirit. There will be no sword anywhere, and everywhere there will be a sword. When you are able to understand this principle, you are almost there.

– calligraphy by Li Jinglin of Guangchuan

–

劒氣如虹劍行似龍

劍神合一玄妙無窮

廣平楊澄甫題

The sword’s energy is like a rainbow.

The sword’s movement is like a dragon.

Sword and spirit merge into one.

The subtleties are without limit.

– calligraphy by Yang Chengfu of Guangping

–

劍術一道源流最遠惜日久失其真之微廣川李公承三峯之嫡傳神心施化運實於虚参两间之消息契二氣之流行劍術至此嘆觀止矣黃君文叔於學劍之後分所記之他日風引海內定求紙貴洛陽也

江蘇東淘吳心穀拜題

The sword art began in the distant past. Alas, the true subtlety of it was lost long ago. Li Jinglin of Guangchuan carries on the teachings of Zhang Sanfeng, that of the mind performing adjustments, switching fullness to emptiness or emptiness to fullness, and examining the interaction between the passive and active energies to make them flow together in harmony. His skill is supreme! Huang Yuanxiu has made a record of everything he has learned in the sword art. It will spread through the nation and is sure to be very popular.

– calligraphy by Wu Xingu of Dongtao [old name for Dongtai], Jiangsu

–

剑與身合為一所谓神而明之存乎其人者

孫福全題词

Sword and body become one.

This is a divine level of understanding

which depends entirely on yourself.

– calligraphy by Sun Fuquan [Lutang]

–

劍術為中國最古之技術歷来為重文輕武之見所湮沒乃者國術日渐昌明谈劍之書隨之而多述法者多述理者少也桂亭自幼好武對於剑術行遍南北未有如李公之玄妙者也曩与黃君文叔同受教於李公朝夕相共頗多记錄今將付梓用誌數語以附偏後

褚桂亭識

Although the sword art is China’s most ancient skill, through the ages it has been the case that literary pursuits were ennobled and martial pursuits were trivialized, and so we have seen it fall into oblivion. But in more recent times, martial arts are gradually beginning to flourish again. Books discussing the sword have consequently increased in number. Most describe techniques, whereas few describe theory. I have adored martial arts since my youth. In regard to the sword, I have traveled all over the nation and found no one whose skill is as profound as Li Jinglin’s. What Huang Yuanxiu and I learned from Li, we worked on together every day, making copious notes. Now the material is about to be published, and I here contribute these brief words.

– written by Chu Guiting

–

幾無為

神變化

庚午杜心五题

Even when there is almost nothing happening,

spirit is still transforming.

– calligraphy by Du Xinwu, 1930

–

李芳宸先生之神劍

Li Jinglin’s “Magic Swords”

李芳宸先生神劍之說明

上圗神劍係合鞘之雙劍,柄長一英寸,刃長約二寸,柄似銅製,刃似鋼製,鞘壳全銅製,晶瑩奪目,清雍正時劍俠所用原秘藏於宫內,共有十三具,迨民國肇興,清社既屋,故宮寳物,漸次失散,此劍展轉入於李師手李師曰,前人練習此劍,能呑之入腹,縱入飛空,李師亦欲練之,惜未從陳世鈞先生竟其學,然觀其質堅鋒利,精光寒爍,洵神品也

Explanation:

The magic swords in the photo above are double swords that fit together into the scabbard. The handles are each one inch long, the blades each two inches long. The handles seem to be made of copper and the blades seem to be made of steel. The scabbard is entirely made of copper, glittering and dazzling. During the reign of Qing emperor Yongzheng [1722-1735], sword heroes stored away a total of thirteen of these items in the palace. When the Republic was established and Qing society was shrunken to a mere house, the treasures in the imperial palace were gradually scattered, and these swords passed through many hands until coming to Li.

He said: “When our predecessors practiced with these swords, they were able to swallow them down and fly up into the sky.” He too wished to try this, but unfortunately he did not complete his training with Chen Shijun. We can observe however from their hardness and their sharpness, their gleam and their shine, that truly they constitute a masterpiece.

[It must be assumed that Huang got to handle these swords in person, since we get little more from this inadequate photo than an unfortunate sense of cheap plastic toy.]

–

李芳宸先生之像

Portrait of Li Fangchen [Jinglin]

–

編者黃元秀之像

Portrait of the author, Huang Yuanxiu

–

書中對劍者褚桂亭之像

Huang’s partner in the photos of this book, Chu Guiting

–

敍

PREFACE

邃古文人率嫻武事三尺龍泉與琴書並稱度當時劍術必甚溥遍秦漢而還右文成習武事銷沉逢掖之士力不能縛雞遑論使用武器故劍術之傳僅深山窮谷間高人逸士相與授受而已因此高尚而溥及之武技寖假湮沒無聞至可慨也愚幼讀詩書壯歲好武囊在軍校肄業時擊劍之技列為專科教授無人借材異域日人松島良吉愚嘗受教擊刺劈斫頗矜其能厥後漫遊東瀛邂逅彼邦劍術能者小倉延猛暇時請益覺其技術精妙逈異凡流從之習未竟其業而返國斯時明知若輩竊我緒餘轉而驕我顧我自無人傳習致興材難之嘆與人何尤雖然莽莽神州遽謂劍術專家竟爾絕跡終未能信以故荏苒十餘年心恆耿耿亦嘗旁搜博訪冀一遇其人一覘吾國固有之劍術特是專家難得愜意者寡論劍之書更無從覓取失望極矣丙丁之交朝野上下競言國術聘河北李芳宸將軍南來主持中央國術館於是京滬人士始得目覩李將軍之劍術驚人競相傳述戊辰秋浙中籌備全國國術遊藝大會將軍任評判委員長愚專誠晉謁備耹中國劍術之源流沿革親見將軍之身手劍法是誠十餘年來欲求一見而不得者大喜過望不揣譾陋從習多日覺其湛深精妙不可言喻用將口授要訣筆之於書聊備遺忘同學諸子以其便於初習慫恿付梓以廣流傳爰敍其緣起於篇首邦人君子幸辱教之十九年夏月黃文叔序

Ancient scholars typically also had martial skills. Wielding a three-foot “dragon well” sword was looked upon as being of the same level as skill in music and calligraphy, and so the sword art in those days was of course extremely pervasive. With the coming of the dynasties of Qin and Han, literary arts became seen as the more worthwhile study, and thus martial skills were trimmed back and sank away. Scholars became so weak, they received help from others to get around. They could not have tied up a chicken, much less wielded a weapon. Therefore the transmission of the sword art continued only in remote mountains and distant valleys where lofty persons who had retired from the world shared it with each other. Consequently, this noble and previously universal martial skill gradually sank into oblivion, leaving us to sigh with regret.

In my youth, I studied poetry and classical literature, but as I matured, I fell in love with martial arts. When I packed my bag and went off to commence my military studies, the skill of sword fighting was listed in the academy as a specialized subject. But as there were no instructors for this course, foreign talent was borrowed by way of a Japanese man named Ryokichi from Matsushima. I learned from him how to strike, stab, chop, and slash, and became rather arrogant about my abilities. I later went to Japan and encountered among their sword experts a man named Nobutake from Kokura. Having some time to myself, I requested instruction from him. His skill seemed to me to be exquisite and very unique. I trained from him for a while, but could not complete my studies with him because I then had to return to China.

I had become fully aware by then that you Japs had sneaked from our material and then pretended to invent it in order to show yourselves superior to us. But when I had considered how nobody was teaching it here and I had groaned over the difficulty of inspiring such talent, it was clear that you were not the ones to be reproached. Even though China is vast, suddenly all of its sword masters seemed to have vanished. I could not yet accept that, and more than ten years slipped by as I persisted in my faith that I would seek out and find someone somewhere who possessed a wealth of knowledge. I hoped I would meet such a person and observe the innate sword art of our nation. But experts who were at a satisfactory level were so extremely rare and books of sword theory rarer still. And I finally gave up all hope.

Then in early 1927, it was announced there were to be national and regional martial arts competitions, and that General Li Jinglin of Hebei was invited to come south and manage the Central Martial Arts Institute. Thereupon people from Beijing and Shanghai started pushing each other aside to get a glimpse for themselves of Li’s astonishing sword skill. In the autumn of 1928, the National Martial Arts Gathering was to be held in Zhejiang, and Li was appointed as head judge. I attended with the specific purpose of gaining an audience with him. I got to listen to him explain the beginnings and development of our nation’s sword art, as well as personally see his methods of body, hand, and sword. This was truly what I had wished to see and had been so unsuccessful in finding for more than ten years.

I was pleased beyond all the hopes I ever had. I also discovered how shallow and crude my own skill really was at the time, and have since been learning from Li. I find his skill to be so deep and refined that I can hardly express it in words, not even by way of analogy. Instead I have put his own oral teachings into a book, in order to prevent them from being forgotten. My classmates have all said it would make the training easier for beginners and have urged me to publish it and have it widely circulated. Hence I have made this account of how this project started. My fellow countrymen, I hope you will honor me with instruction wherever I have made errors.

– written by Huang Wenshu [Yuanxiu], second month of summer, 1930

–

武當劍法大要目錄

CONTENTS

一 劍法述要

One: Stating the Essentials of the Sword Art

二 練劍之五戒

Two: Five Things to Avoid When Training in the Sword Art

三 劍法十三勢

Three: The Sword Art’s Thirteen Techniques

四 十三勢詳解圖説

Four: The Thirteen Techniques with Explanations & Photographs

五 武當劍手法陰陽圈

Five: Wudang Sword’s Hand Positions Modeled Upon the Yinyang Circle

六 分級練習法

Six: Stages of Training

七 對劍三角法

Seven: Two-Person Sword Triangles

八 陰陽劍圈法

Eight: Passive & Active Sword Circles

九 武當劍各套對練法

Nine: Wudang Sword Sparring Set

十 活步對劍

Ten: Lively-Stepping Sparring Set

十一 散劍法

Eleven: Free Sparring Methods

十二 心空歌

Twelve: Central Emptiness Song

十三 練劍歌

Thirteen: Sword Practice Song

十四 練劍之基本

Fourteen: The Fundamentals of Sword Practice

十五 練劍之精神

Fifteen: The Spirit of Sword Practice

十六 用劍之要訣

Sixteen: Secrets of Using the Sword

十七 製劍

Seventeen: Customized Swords

十八 眼法身法手法步法之實習

Eighteen: How to Practice the Eye Movements, Body Standards, Hand Techniques, and Footwork

–

武當劍法大要

ESSENTIALS OF THE WUDANG SWORD ART

李芳宸老師口授 虎林黃元秀初稿

(as taught by Li Jinglin, recorded by Huang Yuanxiu of Hulin)

–

一 劍法述要

ONE: STATING THE ESSENTIALS OF THE SWORD ART

劍術之道。全憑乎神。神足而道成。練精化氣。練氣化神練神成道。劍神合一。是近道矣。

武當劍法。外兼各家拳術之長。內練陰陽中和之氣。習此道者當以無漏為先。保精養氣。寧神抱一。同時學習內家拳為之基礎。基礎既立。然後練習劍法。方得事半功倍。蓋使劍亦如使拳。不外意氣為君。而眼法手法步法身法腰法為臣。是故令其閃展騰拿之輕靈便捷。則有如八卦拳其虛領頂勁。含胸拔背。鬆腰活腕。氣沉丹田。力由脊發則有如太極拳。而其出劍之精神。勇往直前。如矢赴的。敵劍未動,我劍已到。則又如形意拳也。

The way of the sword art is entirely a matter of spirit. When your spirit is abundant, the way has been achieved. Train your essence and transform it into energy. Train your energy and transform it into spirit. Train your spirit and achieve the Way. With sword and spirit merged as one, you will approach the Way.

The Wudang sword art externally draws from the best aspects of various boxing arts and internally trains the balancing of the passive and active aspects to bring about an energy of neutrality. The prerequisite to training in this art is to not give in to the passions. Instead protect your essence, nourish your energy, calm your spirit, and embrace oneness. Also, get a good grounding for it by learning internal boxing arts. Having prepared yourself thus, you may then practice the sword art. This way you will gain twice the result for half the effort, for you will use the sword in the same way as you would apply the boxing, which amounts to nothing more than putting intention and energy in the position of ruler, and the eye movements, hand techniques, footwork, body standards, and waist actions in the position of subject [i.e. mind in charge of body].

As you dodge and extend, surprise and capture, perform these things with great nimbleness and dexterity. In this way, it is like Bagua Boxing.

Forcelessly press up your headtop, contain your chest and pluck up your back, loosen your waist and liven your wrist, sink energy to your elixir field, and issue power from your spine. In this way, it is like Taiji Boxing.

The spirit of thrusting out the sword is courageous and direct, like an arrow loosed toward a target. Before the opponent’s sword has moved, mine has already arrived. In this way, it is like Xingyi Boxing.

–

二 練劍之五戒

TWO: FIVE THINGS TO AVOID WHEN TRAINING IN THE SWORD ART

古來於技術一道。輕視學理。偏重實驗。凡百技術。莫不皆然。而於劍術尤甚。但劍術未練之先。須嚴守五戒。不然若犯其一戒。非徒無益。而有害也。

Since time immemorial, in the method of developing a skill, theory was looked upon lightly and experience was given weight. With all skills, this was always the case, and in the sword art especially so. But before you begin training in the sword art, you must strictly observe five prohibitions. Otherwise, if you violate even one of them, not only will there be no benefit, there may even be harm.

第一戒色慾

First Prohibition – LUST & AVARICE

色者。女色與手媱。學劍者。最為禁忌。練習之時。首重精神。有精而後有氣。有氣而後有力。有力而後有神。慾者。貨利之慾。學者亦宜克制。首編所云。練精化氣。練氣化神。練神成道。又曰保精養氣。寧神抱一。此為劍術界宗教界。奉為千古不易之論。亦人生養生之要道也。

Lust is the craving for women or masturbation. As a student of the sword, this is the crucial thing for you to avoid. When training, of primary importance is vitality. If you have essence, then you have energy. If you have energy, then you have strength. If you have strength, then you have spirit. Avarice is the desire for money and wealth. You should exercise restraint. As was stated in the previous chapter: “Train your essence and transform it into energy. Train your energy and transform it into spirit. Train your spirit and achieve the Way… Protect your essence, nourish your energy, calm your spirit, and embrace oneness.” In both sword art communities and religious circles, this is accepted as an eternal and unchanging truth, an essential principle for life and health.

第二戒殘暴

Second Prohibition – BRUTISHNESS

歷來名將豪俠。練習武術。首重德行。大則為國干城。為民造福。小則捍衛鄉黨。除暴安良。所為澤及當時。名留後世。非用於叛逆草竊。好勇鬭狼等事也。

Throughout history, the famous soldiers and heroes have been gallant men. In training martial arts, also of primary importance is virtuous conduct. On the greater scale, they defended their country to benefit the people, and on the lesser scale, they defended their villages to drive out bullies and bring peace to their families and neighbors. And so the good they did in their time sets an example for future generations. Do not use the art in revolt against your country or in crime against your countrymen, or to get into fights to show off how brave or tough you are.

第三戒躐等

Third Prohibition – IMPATIENCE

凡習武術。無論何門何派。皆由淺而深。由簡而繁。劍術亦然。先練眼法身法手法步法。(此為外四要)次練膽力內勁速力沉着。(此為內四要)按級習練。先求開展。後求緊湊。循序漸進。方臻妙用。

Always in practicing martial arts, regardless of school or style, one goes from the shallows to the depths, from the simple to the complex, and likewise in the sword art. First train the methods of eye, body, hand, and step (these being the four external requirements). Then develop your courage, power, speed, and calmness (these being the four internal requirements). Restrict yourself to the stages of training, first seeking the gross movement and then the finer details. Proceeding step by step, you will then attain a wondrous ability.

第四戒過分

Fourth Prohibition – EXCESSIVENESS

劍術之妙用無窮。而一身之精力有限。故一日之練習。以一日之飲食休養為衡。飲食以補其精。休養以復其神。精神飽滿。則功夫亦隨而長進。故大飢大飽之時。不宜練習。練習疲勞之時。則宜散步換氣。靜座調息。如是調節。庶不致進鋭退速也。

The wonders of the sword art are limitless, but the body’s vitality is limited. This is because one day’s practice is based on one day’s sustenance and rest. Food repairs the essence. Rest restores the spirit. When your essence and spirit are abundant, then your skill will naturally develop. But when you are either overly hungry or overly full, you should not practice, or when you become fatigued in your practice, then you should go for a walk to get some fresh air, or quietly sit to regulate your breath. Moderating in this way, all of your practice will not end up a situation of rapid progress leading to rapid regress.

第五戒無恆

Fifth Prohibition – INCONSTANCY

學劍者。當發義俠心。堅毅心。勇敢心。孔子曰。人而無恆。不可以作巫醫。況學劍乎。勿謂身弱而自餒。勿謂質鈍而中止。勿因事繁而中輟。勿為環境而中斷。天下事。有志者事竟成。聖人之言。勿我欺也。願學者。三復斯言。

A student of the sword should express chivalry, an indomitable will, and courage. Confucius said [Lun Yu, 13.22]: “A man who is inconstant cannot become a shaman.” How much more so in learning the sword art! Do not complain you are weak and then lose confidence. Do not complain you are stupid and then quit. Do not complain you are busy and then give up halfway. Do not get distracted by life and then stop. As with all things in the world, if you are determined, you can achieve it. Those words from that wise man will not lead us astray. If you wish to learn, ponder them.

–

三 劍法十三勢

THREE: THE SWORD ART’S THIRTEEN TECHNIQUES

武當劍法。大別為十三勢。以十三字名之。即抽帶提格。擊刺點崩。攪壓劈截洗。亦似太極拳之掤捋擠按。采挒肘靠。前進後退。左顧右盼。中定也。此外另有舞劍。未有定式。非到劍術純妙不能學習。非口授面傳。不能領會。

The Wudang sword art basically consists of thirteen techniques, namely drawing, dragging, lifting, blocking, striking, stabbing, tapping, flicking, stirring, pressing, chopping, checking, and clearing. This is the same situation as with Taiji Boxing’s [thirteen dynamics]: plucking, rending, elbowing, bumping, warding off, rolling back, pressing, pushing, advancing, retreating, moving to the left, moving to the right, and staying in the center. Beyond them, there is unchoreographed “sword dancing”. You will not be able to learn it until you have become skillful, nor able to even comprehend it without personal instruction.

–

四 十三勢詳解圖説

FOUR: THE THIRTEEN TECHNIQUES WITH EXPLANATIONS & PHOTOGRAPHS

抽◎有上抽下抽二法

[1] DRAWING (which divides into drawing from above and drawing from below)

其式均為太陰劍。手背向上。手心向下。劍尖向前方敵腕之下或上。往右抽之。順勢而斷其腕也。此時之左手為陰手。戟指向前作半圓形。身體偏右。故右足實。而左足虛。即第一套上節。下手之下抽是也。如第一圖之下手抽腕刺式。

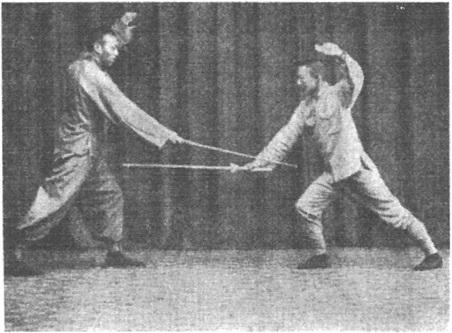

Both versions use the full passive grip, the back of your hand facing upward, center of your hand downward. [The different grip alignments are explained below in the following diagram-only chapter.] With your sword tip forward, either below or above your opponent’s wrist, draw to the right, seizing the opportunity to cut his wrist. Your left hand is now the passive hand, and its “spearing finger” is pointing forward, making a semicircle. Your body is inclined to the right. Your right foot is full, left foot empty. Drawing from below occurs in the earlier part of Section One of the sparring set [outlined below in the ninth chapter]: “Person B, do a drawing cut to Person A’s wrist, then stab.” See photo 1:

〇若作第一套。下節之上手上抽時。左手扶助右手。向右而行。如第二圖之上手抽腕式。

Drawing from above occurs in the later part of Section One of the sparring set: “A, do a drawing cut to B’s wrist.” As you do the drawing cut to your opponent’s wrist, your left hand assists at your right hand, and you are moving to the right: See photo 2:

又第二套刺腕抽腰式。如第三圖之下手。

The version below occurs in Section Two of the sparring set: “Stab to his wrist, then do a drawing cut to his waist.” See photo 3:

又第二套下節之抽腿式。如第四圖之下手。

The version below occurs in the later part of Section Two of the sparring set: “Do a drawing cut to his leg.” [He evades this by lifting his leg.] See photo 4:

帶◎有直帶平帶二法

[2] DRAGGING (which divides into vertical-blade dragging and horizontal-blade dragging)

直帶。為中陰手。手心正中。劍向前方敵腕之下。身向後仰。順勢向後帶其腕而傷之。此法破敵上來(灌耳擊頂)等劍。右足在前變虛。左足在後變實。左手扶助右手劍柄而行之。如第一套第五圖之上手帶腕式。

Vertical-blade dragging uses the half passive grip, the center of the hand centered [i.e. facing to the left]. Your sword goes forward under your opponent’s wrist, your body leaning back. Taking advantage of the fact that you are going to the rear, drag along his wrist to injure him. This technique is for upsetting an incoming attack, the attack being the “filling the ear” strike to the head. Your right foot in front becomes empty and your left foot behind becomes full. Your left hand assists at your sword handle and moves along with it. This occurs in Section One of the sparring set: “A, do a dragging cut to B’s wrist” See photo 5:

又第四套下手直帶式。左手戟指向後。左足實。右足虛。如第六圖。

This also occurs in Section Four of the sparring set: “B, do a vertical-blade dragging cut.” Your left hand’s spearing finger points to the rear. Your left foot is full, right foot empty. See photo 6:

平帶。即陽劍圈。為太陽劍。手心向上。手背向下。劍尖向前方敵腕之下或上。向左平帶。趁勢傷其腕。〇如第四套下節之上下手進退抽帶式。左手扶助右手。先抽而後帶。左足實。右足虛。如第七八兩圖。

With horizontal-blade dragging, perform active sword circling [as in the eighth chapter below] with a full active grip, the center of the hand facing upward, the back of the hand facing downward. With your sword tip going forward either under or above your opponent’s wrist as the sword drags across to the left, take advantage of the opportunity to injure his wrist. This occurs in the later part of Section Four of the sparring set: “Both of you, advance and retreat with drawing and dragging.” With your left hand assisting your right hand, first draw, then drag. Your left foot is full, right foot empty [as in photo 8]. See photos 7 [drawing] & 8 [dragging]:

又第四套上節之對陽劍圈。亦為平帶法。左手扶助右手劍柄。先刺而後帶。此時右足在前是實。左足在後是虛。如第九十兩圖。

This also occurs in the earlier part of Section Four of the sparring set: “Both of you, perform active sword circling.” This is also horizontal-blade dragging. With your left hand assisting at your sword handle, first stab and then drag. At this moment [photo 9], your right foot in front is full and your left foot behind is empty. See photos 9 & 10:

又第一套帶劍刺喉式。左手扶助右手。先帶劍而後刺喉。刺時右足在前是實。帶時右足在前變虛。如第十一十二兩圖。

The version below occurs in Section One of the sparring set: “A, do a dragging action to B’s sword, then stab to his throat.” Your left hand assists your right hand as you first drag and then stab to your opponent’s throat. During the stab, your right foot in front is full, and during the dragging, your right foot becomes empty. See photos 11 [dragging] & 12 [stabbing]:

提◎有向前提後提二法

[3] LIFTING (which divides into front lifting and rear lifting)

其式均為老陰劍。而身法有向前向後之分。身法向前者。為前提式。手腕向上。劍尖向敵腕下扎。如提物向上之勢。有時前足是實。如第一套上節。第十三圖之上下手對提式。

This technique uses the three-quarter passive grip. The body’s maneuvering here divides into forward and back. Front lifting is for advancing, your wrist going upward, your sword tip pricking under your opponent’s wrist. It is like lifting something up. Your front foot may be full, as in the occurrence in the earlier part of Section One of the sparring set: “Both of you, make a lifting posture.” See photo 13:

此法有時前足是虛。如第二套上節。第十四圖。上下手對提式此時左手戟指作半圓形。五套中用之最多。學者須手心空。手腕活。方盡其妙。

Or your front foot may be empty, as in the occurrence in the earlier part of Section Two of the sparring set: “Both of you, make a lifting posture.” This is the version that occurs most often in the sparring set. At this time, your left hand’s spearing finger is making a semicircle. You must loosen your grip and liven your wrist for it to work best. See photo 14:

〇如身法向後時。為後提式。右足往後是實。左足在前是虛。左手扶助右手。向後而行。如第十五圖之上下手對提式。(第二套終了之式。)

Rear lifting is for retreating, your left hand assisting your right hand. Your right foot behind fills and your left foot in front empties as you move back. This occurs in the final posture of Section Two of the sparring set: “Both of you, make a lifting posture.” See photo 15:

格◎有下格與翻格二法○

[4] BLOCKING (which divides into blocking from below [reverse blocking] and overturned blocking)

下格。以中陰劍。斜勢由下向上格敵之腕。身體偏向右方。故右足實而左足虛。左手戟指。作半圓形。即第三套下節。上格腕式。如第十六圖。○

For reverse blocking, use a half passive grip to go diagonally upward from below, blocking to your opponent’s wrist. Your body is leaning to the right. Your right foot is full, left foot empty. Your left hand’s spearing finger is making a semicircle. This occurs in the later part of Section Three of the sparring set: “A, block to B’s wrist.” See photo 16:

翻格以避敵近身之劍。而翻格其腕。此法奇險。非身法虛靈。手法圓活者。不可用也。卽第一套翻格帶腰之翻格式。上手行格腕時如十七圖。

For overturned blocking [using a half active grip], deflect your opponent’s sword as it nears your body, aiming for his wrist. This technique is quite risky. If your body technique is not nimble or your hand technique is not lively, you cannot apply it. This occurs in Section One of the sparring set: “B, do an overturned block, then a dragging cut to A’s waist.” See photo 17 (blocking to the wrist):

前右足虛。後左足實。下手行帶腰時。如第十八圖。

With your right foot in front empty [full] and your left foot behind full [empty], now do the dragging cut to the waist. See photo 18 [your opponent now blocking to your wrist]:

前右足實。後左足虛。左手戟指作半圓形。又第三套之格腕帶腰時。如第十九圖。

[As your opponent in turn does the dragging cut to your waist,] his right foot in front is full and his left foot behind is empty, his left hand’s spearing finger making a semicircle. This scenario also occurs in Section Three of the sparring set: “Block to his wrist, then do a dragging cut to his waist.” See photo 19 [with you blocking again to his wrist]:

擊◎有正擊反擊二法

[5] STRIKING (which divides into straight striking and reverse striking)

〇正擊為少陽劍。手腕向上。以劍平行。直前擊敵之腕。如擊罄之勢。右足向前是虛。左足在後是實。左手戟指向後撐。即第二套上節之上擊腕式。如第二十圖。

Straight striking uses the one-quarter active grip. With the inside of your wrist facing upward and your sword blade horizontal, go straight forward to strike your opponent’s wrist as if striking a stone chime. Your right foot in front is empty and your left foot behind is full. Your left hand’s spearing finger braces to the rear. This occurs in the earlier part of Section Two of the sparring set: “A, strike to B’s wrist.” See photo 20:

又第二套下手之擊頂式。如第二十一圖。

The version below occurs in Section Two of the sparring set: “B, strike to A’s head.” See photo 21:

〇反擊。有擊耳擊腕之分。擊耳即俗稱為灌耳。以劍之刃。反擊敵之耳際是也。右足往前是實。左足在後是虛。即第一套中之壓劍擊耳式。第二十二圖。

Reverse striking divides into striking to the ear and striking to the wrist. Striking to the ear is commonly referred to as “filling the ear”. Using the inside edge of your sword, do a reverse strike to your opponent’s ear. Your right foot in front is full and your left foot behind is empty. This occurs in Section One of the sparring set: “Press down his sword, then strike to his ear.” See photo 22:

擊腕。即第三套之扣腕擊如第二十三圖。

Striking to the wrist occurs in Section Three of the sparring set: “Do a covering strike to his wrist.” See photo 23:

又第二套上手反擊腕如第二十四圖。

The version below in Section Two of the sparring set: “A, do a reverse strike to B’s wrist.” See photo 24:

刺◎有側刺平刺二法

[6] STABBING (which divides into vertical-blade stabbing and horizontal-blade stabbing)

側刺。即以中陰劍。上步向前直刺。右足在前是實。左足在後是虛。左手戟指。作半圓形。即第一套之下手抽腕刺式。如第二十五圖。

A vertical-blade stab uses a half passive grip. Step forward, stabbing forward with the blade upright. Your right foot in front is full and your left foot behind is empty. Your left hand’s spearing finger is making a semicircle. This occurs in Section One of the sparring set: “B, do a drawing cut to A’s wrist, then stab.” See photo 25:

又第五套上節下手刺胸。(金雞獨立式)如第二十六圖。

The version below occurs in the earlier part of Section Five of the sparring set: “B, stab to A’s chest (performing GOLDEN ROOSTER STANDS ON ONE LEG).” See photo 26:

又第五套下節下手翻腕刺。如第二十七圖

The version below occurs in the later part of Section Five of the sparring set: “B, turn over your wrist and stab.” See photo 27:

平刺與側刺同。惟劍面作平扁向前行耳。即第一套開始之對平刺式。如第二十八圖。

A horizontal-blade stab is the same as a vertical-blade stab, except the sword goes forward with the blade flat [full active grip]. This is the opening movement in Section One of the sparring set: “Do a horizontal-blade stab toward each other”. See photo 28:

點◎

[7] TAPPING

中陰劍。身臂皆不動。以腕掌之力。使劍尖往下直點敵腕。右足在前是虛。左足在後是實左手。戟指作半圓形如第二十九圖。卽。第一套上節上手之點腕式及第二套下節之上手點腕式。

Using a half passive grip and without moving the rest of your body or arm, apply strength from your wrist to send your sword tip downward, with the blade vertical, toward your opponent’s wrist. Your right foot in front is empty and your left foot behind is full. Your left hand’s spearing finger is making a semicircle. This occurs in the earlier part of Section One of the sparring set: “A, tap to B’s wrist.” And also in the later [earlier] part of Section Two. See photo 29:

崩◎有正崩翻崩二法

[8] FLICKING (which divides into upright flicking and overturned flicking)

正崩。即以中陰劍。身臂皆不動。手持劍柄。使劍尖向上直挑敵腕。右足在前是實。左足在後是虛。左手扶助右手劍柄。使劍尖上崩。即第二套之斜步崩式。如第三十圖。

Upright flicking uses the half passive grip. With your body and arm not moving, your hand sends your sword tip upward, the blade vertical, to attack your opponent’s wrist, your left hand assisting at your sword handle to make the tip flick upward. Your right foot in front is full and your left foot behind is empty. This occurs in Section Two of the sparring set: “Step diagonally and do a stabbing flick.” See photo 30:

〇翻崩在套步中。由下向上。翻手崩敵之腕。卽第一套上節之對翻崩式。如第三十一圖。此點崩二法。全仗丹田內勁行之。

Overturned flicking uses [a half active grip and] a covering step. Coming upward from below with your hand turned over, flick to your opponent’s wrist. (Both tapping and flicking depend entirely on energy from your elixir field.) This occurs in the earlier part of Section One of the sparring set: “Both of you, do an overturned flick toward each other”. See photo 31:

劈◎

[9] CHOPPING

其式持中陰劍。上步向前直劈。卽第三套開始之劈頭式。右足在前是實。左足變虛。左手戟指作半圓形。如第三十二圖。

Using a half passive grip, step forward and chop with the blade vertical. This occurs in the first movement of Section Three of the sparring set: “Chop to his head.” Your right foot in front is full and your left foot behind is empty. Your left hand’s spearing finger is making a semicircle. See photo 32:

截◎有平截左截右截反截四種

[10] CHECKING (which divides into four versions: horizontal checking, left checking, right checking, reverse checking)

平截。即以中陰劍上前截敵之腕。前右足實。後左足虛。第五套上節之抬劍平截式。如第三十三圖。

For horizontal checking, using a half passive [full active] grip, send your sword upward and forward to check your opponent’s wrist. Your right foot is full, left foot empty. This occurs in the earlier part of Section Five of the sparring set: “Raise your sword and do a horizontal check.” See photo 33:

左截者。避敵刺我之劍。身體偏右。而劍向左方截敵刺我之腕。故右足實。而左足虛。卽第一套中節。下手之截腕式。第二套中節上手之截腕式。如第三十四圖。

For left checking, avoid your opponent’s stab by inclining your body to the right while sending your sword to the left to check his wrist. Your right foot is full, left foot empty. This occurs midway through Section One of the sparring set: “B, check to A’s wrist.” And also midway through Section Two: “A, do a left check to B’s wrist.” See photo 34:

右截者。避敵擊我之腕身。向左方以劍回截敵之右腕。故左足實。而右足虛。即第五套之對截式。如第三十五圖。

For right checking, avoid your opponent’s strike to your wrist or body by moving to the left while bringing your sword to the right to check his wrist. Your left foot is full, right foot empty. This occurs in Section Five of the sparring set: “Both of you, check to your opponent’s wrist.” See photo 35:

反截即第五套上節。下手反截腕。左足實。右足虛。身偏左。由上向下而截敵之右腕。如第三十六圖。無論左截。右截。左手戟指作半圓形。

Reverse checking occurs in the earlier part of Section Five of the sparring set: “B, do a reverse check to A’s wrist.” Your left foot is full, right foot empty. Your body inclines to the left as you go downward from above to your opponent’s wrist. (Whichever of the versions, your left hand’s spearing finger is making a semicircle.) See photo 36:

攪◎有橫攪直攪二法

[11] STIRRING (which divides into horizontal stirring and vertical stirring)

橫攪上下手皆為中陰劍。作直角式而攪之。即第一套上手之橫攪式。左手戟指作半圓形。此時上下手在行走中。左右足虛實不定。如第三十七圖。

For horizontal stirring, both you and your opponent use a half passive grip, holding your swords up diagonally, the blades vertical, and stir them around each other. This occurs in Section One of the sparring set: “A, perform horizontal stirring.” Your spearing finger is making a semicircle. You are in the midst of walking around each other during this technique, and so neither left nor right foot stabilizes as either empty or full. See photo 37:

直攪下手變為陽劍時。其劍尖直攪上手之腕。左手扶助右手劍柄直進。即第四套下手之進步攪式。如第三十八圖。

For vertical stirring, switch to the full active grip and bring your sword tip stirring toward your opponent’s wrist, your left hand assisting at your sword handle as you advance. This occurs in Section Four of the sparring set: “B, advance with stirring.” See photo 38:

此時上手作退步姿勢。亦以陽劍劍尖。回攪下手之腕。左手扶助右手劍柄。向後且攪且退。如三十九圖。惟下手攪時。其劍尖之圈小。劍柄之圈大。上手攪時。劍尖圈依下手之腕而攪。自己之腕避下手之劍尖而繞行。

Your opponent is now in a retreating posture, also using a full active grip as his sword tip withdraws and stirs to be under your wrist. His left hand assists at his sword handle as he goes to the rear, stirring while retreating. When you stir, your sword tip is making a smaller circle and your sword handle is making a larger circle. When he stirs, his sword tip circles in accordance with your stirring and where your wrist is, his own wrist circling to avoid your sword tip. See photo 39:

壓◎

[12] PRESSING

即我之陰劍。作直角式壓敵之劍。使其停滯。而我得乘機變化攻擊之也。壓時。我之劍尖。稍向下垂。使敵劍無可逃脱。右足在前是實。左足在後是虛。左手戟指作半圓形。即第一套之壓劍式。如第四十圖。

Using a one-quarter passive grip, press down your opponent’s sword, with your blade diagonally vertical, to slow him down and then take advantage of the opportunity to switch to attacking. When pressing down, your sword tip hangs slightly downward, causing him to be unable to take his sword away. Your right foot in front is full and your left foot behind is empty. Your left hand’s spearing finger is making a semicircle. This occurs in Section One of the sparring set: “Press down his sword.” See photo 40:

洗◎

[13] CLEARING

此式為中陽劍。持劍上步猛進敵身。由下向上倒劈之。右足向前是實。左足在後是虛。左手戟指作半圓形。即第四套之上手洗式。如四十一圖。

This technique uses a half active grip. Step forward and aggressively attack your opponent’s body, going upward from below with a reverse chop. Your right foot in front is full and your left foot behind is empty. Your left hand’s spearing finger is making a semicircle. This occurs in Section Four of the sparring set: “A, do a clearing cut.” See photo 41:

〔註〕劍法無砍砍等名稱有之刀法而非劍法也故劍法當以此十三式為準學者先求各式正確然後再求精熟嗣後熟能生巧此與學書者先求平直務追險絕之語可一例也。

Note:

The sword art is not a matter of hacking. If you are hacking, you are performing saber techniques rather than the sword art. Therefore the sword art is simply these thirteen techniques as a standard. First seek to make each technique correct, then skillful, and then with practice will come artistry. This and the statement in calligraphy of “the student first strives with the simple, then moves on to the difficult” are identical ideas.

–

五 武當劍手法陰陽圈

FIVE: WUDANG SWORD’S HAND POSITIONS MODELED UPON THE YINYANG CIRCLE

[This diagram is rather unhelpful since it is based on the alignment of your hand as seen by someone standing in front of you. It will be much easier to realize the intended positions of your hand as it grips your sword if we flip the image left/right, and in that way I have arranged the terms below:]

中陰

half passive

[tiger’s mouth facing up ↑]

少陰 少陽

[↖] one-quarter passive one-quarter active [↗]

太陰 陰 陽 太陽

[←] full passive [black section] passive / active [white section] full active [→]

老陰 老陽

[↙] three-quarter passive three-quarter active [↘]

中陽

half active

[tiger’s mouth facing down ↓]

[The half passive grip (↑) is the most frequently mentioned hand position in this manual. The three-quarter active grip (↘) is never mentioned at all within this text, though it does appear in Sun Lutang’s 1927 Bagua Sword manual.]

–

六 分級練習法

SIX: THE STAGES OF TRAINING

初級個人單練。二級對套子。三級活步對劍。四級二人對練散劍。

1. solo practice

2. sparring set

3. lively-stepping sparring set

4. free sparring

〔註〕散劍精熟然後一人可以對二人以上之敵人或以一劍對抗長槍大戟神而明之存乎其人矣。

Note:

When you have become skillful at sparring, you may then spar against two or more opponents at the same time, or spar with sword versus long weapon, such as spear or halberd, and then you will be classed among those who achieved an almost magical understanding.

–

七 對劍三角法

SEVEN: TWO-PERSON SWORD TRIANGLES

敵來之劍為截。我應以提。成上三角也。敵來之劍為刺。我應以崩。成下三角也。敵來之劍為攪。我應以帶。成左三角也。敵來之劍為劈。我應以下斜格。成右三角也。三角習熟。而後進以陰陽圈。兩法習熟。始可習散劍矣。

The opponent attacks with checking, so I respond with lifting, thus making a triangle above.

The opponent attacks with stabbing, so I respond with flicking, thus making a triangle below.

The opponent attacks with stirring, so I respond with dragging, thus making a triangle to the left.

The opponent attacks with chopping, so I respond with blocking diagonally downward, thus making a triangle to the right.

When these triangles are practiced to familiarity, then progress to the passive and active circles. Then when both methods have been trained to familiarity, you will be on your way to practicing free sparring.

〔註〕武當劍法甚奇而精華實類乎科學之三角法學者幸勿忽諸

Note:

The techniques of the Wudang sword art are marvelous and refined, but are actually nothing more than trigonometry. Please do not ignore this.

–

八 陰陽劍圈法

EIGHT: PASSIVE & ACTIVE SWORD CIRCLES

手背向上。為之陰劍。陰劍圈。先帶後刺。手心向上。為之陽劍。陽劍圈。先刺後帶。(第四套之上半節是也)手背向上而少斜。為少陰劍。(提劍式)手心向上而少斜。為之少陽劍。(劈劍式)陰陽兩劍圈。皆須單行熟練。此式之要。在身退而劍進。身避而劍刺也。陰手為抽。陽手為帶。(指第四套下半節攪劍後之手法)

With the back of your hand facing upward, full passive grip, perform passive sword circling, which drags then stabs. With the center of your hand facing upward, full active grip, perform active sword circling, which stabs then drags. (This occurs in the first half of Section Four of the sparring set.)

Circle with the back of your hand facing upward and slightly diagonal, one-quarter passive grip (as in lifting). Circle with the center of your hand facing upward and slightly diagonal, one-quarter active grip (as in chopping).

The passive and active sword circles must be drilled as individual exercises. The key to these exercises is that your body retreats evasively but your sword advances with stabbing. These passive grips are for drawing while these active grips are for dragging. (This occurs in the second half of Section Four of the sparring set, after the stirring technique.)

–

九 武當劍各套對練法

NINE: WUDANG SWORD SPARRING SET

第一套

Section One:

上下出劍式。對平刺。(陽手)對翻崩。

[1] A & B, both of you send out your sword with a horizontal-blade stab (full active grip) toward each other [photo 28], then an overturned flick toward each other [photo 31].

上點腕。

[2] A, tap to B’s wrist. [photo 29]

下抽腕刺。

[3] B, do a drawing cut to A’s wrist, then stab. [photo 1 for the drawing cut, then photo 25 for the stab]

對提。對走。

[4] Both of you, make a lifting posture [photo 13], then walk around each other.

下翻格帶腰。上翻格帶腰。重二遍。

[5] B, do an overturned block, then a dragging cut to A’s waist, then A, do an overturned block, then a dragging cut to B’s waist [photos 17 & 18 (19 & 18)] – Do this twice.

下壓劍擊耳。(灌耳)

[6] B, press down A’s sword [photo 40], then strike to A’s ear (“filling the ear”). [photo 22].

上帶腕。(崩勢)

[7] A, do a dragging cut to B’s wrist (with a flicking energy). [photo 5]

對提對劈。

[8] Both of you, make a lifting posture, then chop at each other.

下刺喉。

[9] B, stab to A’s throat.

上帶劍刺喉。

[10] A, do a dragging action to B’s sword, then stab to his throat. [photos 11 & 12]

陽劍圈。

[11] Both of you, perform active sword circling.

上橫攪。

[12] A, perform horizontal stirring. [photo 37]

下擊頭。

[13] B, strike to A’s head.

上擊腿。

[14] A, strike to B’s leg.

下截腕。

[15] B, do a [reverse] check to A’s wrist.

上帶腕。(保門勢)

[16] A, do a dragging cut to B’s wrist (getting into the “guarding the gate” posture [on the other side]).

下左截腕。

[17] B, do a left [right] check to A’s wrist.

上抽腕刺胸。

[18] A, do a drawing cut to B’s wrist, then stab to his chest.

下截腕。

[19] B, [left] check to A’s wrist. [photo 34]

上帶腕。(保門勢)

[20] A, do a dragging cut to B’s wrist (“guarding the gate”).

下翻格。

[21] B, do an overturned block.

上抽腕。

[22] A, do a drawing cut to B’s wrist. [photo 2]

各保門完。

[23] Both of you, adopt the “guarding the gate” posture. This concludes Section One.

第二套

Section Two:

下上步擊。

[1] B, step forward and strike.

上擊腕。

[2] A, strike to B’s wrist. [photo 20]

對提。

[3] Both of you, make a lifting posture. [photo 14]

上刺膝。(箭步)

[4] A, stab to B’s knee (in an arrow stance).

下壓劍帶腰。(箭步)

[5] B, press down A’s sword, then do a dragging cut to his waist (in an arrow stance).

對翻崩。

[6] Both of you, do an overturned flick toward each other. [photo 31]

上點腕。

[7] A, tap to B’s wrist. [photo 29]

下斜刺崩。

[8] B, step diagonally and do a stabbing flick. [photo 30]

上抽。

[9] A, do a drawing cut.

下刺腹。

[10] B, stab to A’s belly.

上左截腕。

[11] A, do a left check to B’s wrist. [photo 34]

對劈。

[12] Both of you, chop at each other.

下反擊耳。

[13] B, do a reverse strike to B’s ear.

上反擊腕。

[14] A, do a reverse strike to B’s wrist. [photo 24]

下抽腿。

[15] B, do a drawing cut to A’s leg. [photo 4]

互刺腕抽腰走。重二次。

[16] Both of you, stab to your opponent’s wrist, do a drawing cut to his waist, then walk around each other [photo 3] – Do this twice.

下擊頭。

[17] B, strike to A’s head. [photo 21]

上帶腕回擊

[18] A, do a dragging cut to B’s wrist, then return a strike.

對。提各。保門完。

[19] Both of you, make a lifting posture, [photo 15] then return to the guarding posture. This concludes Section Two.

第三套

Section Three:

下劈頭。

[1] B, chop to A’s head. [photo 32]

上格劍帶腰。

[2] A, block B’s sword, then do a dragging cut to his waist.

下格腕帶腰。

[3] B, block to A’s wrist, then do a dragging cut to his waist. [photo 19 (17)]

上格腕帶腰。

[4] A, block to B’s wrist, then do a dragging cut to his waist.

下格腕帶腰。

[5] B, block to A’s wrist, then do a dragging cut to his waist.

上格腕。

[6] A, block to B’s wrist.

下壓劍。反擊耳。(灌耳)

[7] B, press down A’s sword, then do a reverse strike to his ear (“filling the ear”).

上直帶。(崩勢)

[8] A, do a vertical-blade dragging cut (with a flicking energy).

下提。

[9] B, make a lifting posture.

上上步扣腕擊。

[10] A, step forward and do a covering strike to B’s wrist. [photo 23]

下上步扣腕擊。

[11] B, step forward and do a covering strike to A’s wrist.

對走。對反抽。

[12] Both of you, walk around each other, then withdraw your swords.

下刺腹。

[13] B, stab to A’s belly.

上格腕。

[14] A, block to B’s wrist. [photo 16]

對繞腕。各保門完。

[15] Both of you, arc toward your opponent’s wrist, then return to the guarding posture. This concludes Section Three.

第四套

Section Four:

上洗。

[1] A, do a clearing cut. [photo 41]

下陽劍圈起手。

[2] B, perform active sword circling, your hand lifted.

對陽劍圈。

[3] Both of you, perform active sword circling. [photos 9 & 10]

下陰劍圈起手。

[4] B, perform passive sword circling, your hand lifted.

對陰劍圈。

[5] Both of you, perform passive sword circling.

下進步攪。

[6] B, advance with stirring. [photo 38]

對攪

[7] Both of you, stir. [photo 39]

下抽。

[8] B, do a drawing cut.

上下進退抽帶。重三遍。

[9] Both of you, advance and retreat with drawing and dragging [photos 7 & 8] – Do this three times.

下崩。

[10] B, flick.

上抽。

[11] A, do a drawing cut.

下上步刺。

[12] B, step forward and stab.

互壓劍。

[13] Both of you, press down your opponent’s sword.

上擊腿。上反擊耳。

[14] A, strike to B’s leg, then do a reverse strike to his ear.

下直帶。

[15] B, do a vertical-blade dragging cut. [photo 6]

對提。各保門完。

[16] Both of you, make a lifting posture, then return to the guarding posture. This concludes Section Four.

第五套

Section Five:

對伏式。

[1] Both of you, get into a crouching posture.

上刺。(中陰手)

[2] A, stab (half passive grip).

下擊腕。

[3] B, strike to A’s wrist.

上抬劍平截。

[4] A, raise your sword and do a horizontal check. [photo 33]

對截腕。

[5] Both of you, check to your opponent’s wrist. [photo 35]

對提。對走。

[6] Both of you, make a lifting posture, then walk around each other.

上正崩。(中陰手)

[7] A, do an upright flick (half passive grip).

下帶腕。(保門勢)

[8] B, do a dragging cut to A’s wrist (putting you into the guarding posture).

上進步反格。(中陰手)

[9] A, advance and do a reverse block (half passive grip).

下抽身截腕。

[10] B, withdraw your body, then check to A’ wrist.

上上步截腕。

[11] A, step forward and check B’s wrist.

下反截腕。

[12] B, do a reverse check to A’s wrist. [photo 36]

上抽手截腕。

[13] A, withdraw your hand, then check to B’s wrist.

下抽手截腕。

[14] B, withdraw your hand, then check to A’s wrist.

上帶腿換步刺腰。

[15] A, do a dragging cut to B’s leg, then switch feet and stab to his waist.

下換步刺腰。

[16] B, switch feet and stab to A’s waist.

上平抽。

[17] A, do a horizontal drawing cut.

下刺胸。(獨立金雞式)

[18] B, stab to A’s chest (performing GOLDEN ROOSTER STANDS ON ONE LEG). [photo 26]

上平帶。

[19] A, do a horizontal-blade dragging cut.

對提。各保門。各伏式。

[20] Both of you, make a lifting posture, return to the guarding posture, then get into a crouching posture.

下刺胸。

[21] B, stab to A’s chest.

上平擊。

[22] A, do a horizontal strike.

對提。

[23] Both of you, make a lifting posture.

對劈。

[24] Both of you, chop at each other.

對刺。

[25] Both of you, stab at each other.

上格腕。

[26] A, block to B’s wrist.

下翻腕刺。

[27] B, turn over your wrist and stab. [photo 27]

上扣腕刺。

[28] A, do a covering stab to B’s wrist.

對轉身劈劍式各保門。上下收劍式完。

[29] Both of you, turn your body, chopping at each other, return to the guarding posture, then finish with the closing posture.

以上所編套子。卽以十三式。應用方法變化而成。對練時。審來度往。按法練習。初習時。宜慢不宜快。宜緩不宜疾。式式應到家。劍劍須着實。有時須注意用法。與練法不同處。此其大概也。

This sparring set is constructed of the thirteen techniques – the ways they are applied and the ways they adapt to each other. When practicing this sparring set, examine what comes at you and consider what you will send out, always acting in accordance with your training in those techniques. When beginning to learn this set, it should be slow instead of fast, deliberate instead of rushed. Your postures should be perfect and your techniques should be genuine. Sometimes during the set, you will have to take note of the difference between combat and training, and that the training in this set will give you only a general sense of it.

〔註〕此卽兩人對練套子上下手不同故須一人習上手一人習下手學者宜對練精熟然後互易上下手如上手熟改習下手習下手者改習上手庶幾一人兼會兩法師門所傳現祇六大段約言之則為六套故曰套子對練法

Note:

Since A and B do different things, one person should learn one role while another learns the other. You should both practice your roles until you are thoroughly familiar with them, then trade places. Once A is skillful at being A, he changes to become B, and B changes to become A. Hopefully each person will then come to know both roles equally. Of this material, what Li Jinglin passed down amounts finally to only these six large sections [including the extra material below in the tenth chapter]. Simply put, these six parts form the sparring sets [of Wudang Sword].

–

十 活步對劍

TEN: LIVELY-STEPPING SPARRING SET

上下手出劍式。上下手對刺。

[1] A & B, both of you perform the initiating posture, then stab toward each other.

上套步壓劍。上上步灌耳。

[2] A, perform a covering step while pressing down B’s sword, then step forward performing “filling the ear”.

對格腕帶腰走。

[3] Both of you, block to your opponent’s wrist, then do a leading cut to his waist, then walk around each other.

上擊耳。(灌耳)

[4] A, strike to B’s ear (“filling the ear”).

下擊腕。下擊耳。(灌耳)

[5] B, strike to A’s wrist, then to his ear (“filling the ear”).

上擊腕走。

[6] A, strike to B’s wrist, then both of you walk around each other.

上下雙擊耳。上下對刺腕。對擊頭。對橫攪。

[7] Both of you, strike to your opponent’s ear, then stab to his wrist, then strike to his head, and perform horizontal stirring.

上截腿。

[8] A, check to B’s leg.

下擊腕。

[9] B, strike to A’s wrist.

對陽劍圈。對陰劍圈。對直攪。

[10] Both of you, perform active sword circling, then perform passive sword circling, then perform vertical stirring.

下刺。

[11] B, stab.

上帶。

[12] A, do a dragging cut.

各對刺。

[13] Both of you, stab.

上左手按。

[14] A, push out with your left hand.

下掃堂。

[15] B, perform “sweeping the hall”.

上跳步擊頭。

[16] A, jump and strike to B’s head.

下回擊腕。

[17] B, do a reverse strike to A’s wrist.

上平帶腰。上轉身擊腕。

[18] A, do a horizontal-blade dragging cut to B’s waist, then turn around and strike to B’s wrist.

下轉身擊腕。下擊耳。

[19] B, turn around and strike to A’s wrist, then to his ear.

上刺腕。

[20] A, stab to B’s wrist.

保正門。上下收劍式完。

[21] Both of you, return to “guarding the main gate”, then finish with the closing posture.

–

十一 散劍法

ELEVEN: FREE SPARRING METHODS

練散劍。分三種方法。第一原地對擊法。活用手腕。與人擊刺。使心眼手三者合為一氣是也。第二行動對擊法。以手法步法與人對擊。第三活用身法。手法。步法。忽前忽後。聲東擊西。或上或下。奔騰飄忽。劍行如電。身行如龍是也。

Free sparring divides into three methods:

1. Standing in one place and stabbing at each other, emphasizing the suppleness of the wrist. This gets mind, eye, and hand to work together as one.

2. Walk around, attacking each other using both hand techniques and footwork.

3. Make use of hand techniques, footwork, and body maneuvering. Suddenly go forward, then suddenly back. Draw attention to one side, then attack the other. Be above, then below. Then rush in, taking him by surprise. Your sword moves like lightning. Your body moves like a dragon.

〔註〕散劍如拳家之散手備實用之動作也未嫻散劍不可與人對劍然套子活步對劍等等無相當功夫者決不可先習散劍是以戒躐等也

Note:

Free sparring with swords is like empty-hand free sparring in that it too prepares you for real situations. If you are not yet adept at free sparring with a sword, you cannot yet engage in sword fighting. However, if you are not up to a good standard of skill in the lively-stepping sparring-set, you cannot even begin to practice free sparring. This is why skipping ahead in the training is forbidden.

–

十二 心空歌

TWELVE: CENTRAL EMPTINESS SONG

歌曰。手心空。使劍活。足心空。行步捷。頂心空。身眼一。

When the center of the hand is empty, it makes the sword lively.

When the center of the foot is empty, it makes the step nimble.

When the center of the headtop is empty, it makes body and eye work as one.

–

十三 練劍歌

THIRTEEN: SWORD PRACTICE SONG

頭腦心眼如司令。手足腰胯如部曲。內勁倉庫丹田是。精氣神膽須充足。內外工夫勤修練。身劍合一方成道。

Your mind is like a commanding officer,

and your hands, feet, waist, and hips are like his troops.

With internal power being stored in your elixir field,

there is sure to be sufficient essence, energy, spirit, and courage.

When both internal and external skill are ardently cultivated,

your body and sword merge into one, and thereby the Way is achieved.

〔註〕丹田譬猶倉庫蓄內勁之所也身劍合一者劍恍如其人肢體之一部凡其人之內勁能直貫注劍鋒則其鋒不可犯也

Note:

Your “elixir field” is like a warehouse. It is where internal power is stored up. Your body and sword merging into one means that your sword has become like a part of your body. Your internal power should always be able to penetrate straight to the sword tip, turning it into something that must be avoided.

–

十四 練劍之基本

FOURTEEN: THE FUNDAMENTALS OF SWORD PRACTICE

一眼神。二手法。三身法。四步法。

1. eye movements

2. hand techniques

3. body standards

4. footwork

–

十五 練劍之精神

FIFTEEN: THE SPIRIT OF SWORD PRACTICE

一膽力。二內勁。三迅速。四沉着。

1. courage

2. inner power

3. decisiveness

4. imperturbable calm

劍法之基本。外四要也。劍法之精神。內四要也。內外精健。庶乎近焉。

The fundamentals are the four external essentials. The kinds of spirit are the internal essentials. When the internal and external are perfected, you will be almost there.

〔註〕內勁云示與蠻勁拙力不同但無悠久之功夫無正確之教練無持久之毅力決無成績可言是以練劍者長習內家拳以蓄內勁內勁之云其所由來者漸非一朝一夕所能致也。

Note:

Internal power is not at all like the clumsiness of ferocious strength. However, without long-term training, proper teaching, and willpower, you will never be able to proclaim success. Therefore practitioners of the sword art engage in long practice of internal boxing arts to store up internal power. Internal power comes about gradually and cannot be attained in a day.

–

十六 用劍之要訣

SIXTEEN: SECRETS OF USING THE SWORD

用劍之要訣。全在觀變。(眼神)彼微動我先動。(手法)動則變。(身法)變則着矣。(步法)此四句皆在一箇字行之。所為一寸七。所謂險中險。(膽力)卽劍不離手。(迅速)手不着劍是也。(沉着)

It is entirely a matter of seeing the situation evolve. (This has to do with the eye movements.)

“Once he takes even the slightest action, I have already acted.” (This has to do with the hand techniques.)

“With movement there is adaptation.” (This has to do with the body standards.)

“And with adaptation there is transformation.” (This has to do with the footwork.) [Huang considered these quotes to be from Yang Jianhou.]

Eye, hand, body, and step all come down to a single word: movement. To be as close as two inches is a very dangerous range indeed. (This has to do with courage.)

The sword does not leave your hand, nor does your hand touch the sword. (This has to do with your decisiveness and composure.)

〔註〕劍為短兵器中之王三面皆刃故其用法與單刀迥異時下流行之劍法大率羼入刀法雖劍光耀目實類花刀不足稱也

Note:

The sword is called the “king of short weapons”, for every edge of the blade is a cutting edge. Therefore its use is very different from a saber. The currently fashionable sword methods are mostly drawn from saber methods, and no matter how dazzling such swordwork is, it is really just flashy saber-wielding, unworthy of praise.

–

十七 製劍

SEVENTEEN: CUSTOMIZED SWORDS

古來名將豪俠。所用之器械。大小輕重不一。其衝鋒陷陣。殺敵致果與否。全視乎藝術之精疏。與環境之如何耳。非大者定能勝小。重者定能勝輕。稍明武術歷史者。無不深知也。

人身秉賦不同。生長各異。故所用之器械。長短輕重。全視其人之大小而異。總以運用靈活。指揮如意。為合用。其次研究質料之精粗。與裝配之良好。武當劍之劍把。與通常劍把不同。其形狀如向上之稜角。於劍法上有特別作用。其一可以抗敵之劍。其二可以利用敵劍之力。而傷敵之身手。其妙用全在陰陽二法中。非為美觀而裝飾也。此初習武術者。急應注意。否則於急遽之中。未能得心應手也。

武當劍。分練習劍。與實用劍兩種。練習劍。為粟樹或檀木製。實用劍為純鋼製成。

練習劍凡人生長在六尺以下。體重在百二十斤以內者。為之通常體格。其練習之木劍。全長為三尺乃至三尺六寸。(英尺)劍柄長六寸。乃至八寸。其重十四兩乃至十八兩。其重點在全長之中心。過輕不能增長腕力。過重反將臂腕練拙。不得虛靈圓活之妙用矣。如四十二圖。

The famous generals and heroes of ancient times wielded weapons that differed in size and weight. Whether or not they could charge toward enemy lines and come away victorious entirely depended on perfection of skill and awareness of their surroundings. It was never the case that the larger was bound to defeat the smaller or the heavier was bound to defeat the lighter. With a slight understanding of martial arts history, anyone will fully realize this.

Our bodies are all different right from the start and develop to become even more different Thus the differences in the length and weight of the weapons we use entirely depend on our body size, and it is always the case that the weapons most fitting for our use are the ones we can wield with nimbleness and control with ease. We are then to consider the quality of the material used in its making and if it is put together the way we would like. The Wudang sword hilt for instance is different from the norm, the corners angled upward for the special purposes of catching the opponent’s sword and taking advantage of his force to injure his body or hand.

Skill is entirely a matter of using the duality of passive and active, not trying to impress people with flashy maneuvers. Martial arts beginners should strongly give attention to this point. If not, then when you find yourself in an emergency, you will not be able to make your sword do what you want.

The Wudang sword art divides into the use of a training sword and a performance sword. The training sword is made from either chestnut or sandlewood, whereas the performance sword is made from purified steel.

For a training sword, if you are below six feet and under a hundred and twenty pounds, you are of a normal build. Your wooden training sword should in overall length be between three feet (English feet) and three feet, six inches. The sword handle should be between six inches and eight inches. The weight should be between fourteen and eighteen ounces. The center of balance should at the center of the entire length. If it is overly light, you will not be able to increase your wrist strength. If on the other hand it is overly heavy, it will cause your forearm and wrist to become habitually awkward, and you will be unable to obtain a lively and nimble skillfulness. See photo 42:

實用劍。以純鋼彈力劍為佳。通常體格者。其長短與學習劍相等。其重量。較學習劍減輕八折為適當。如過長過重。皆非所宜。重心須近手柄。否則不便使用。如四十三圖。

For a performance sword, ideally it should be a steel sword with some springiness to it. If you are of a normal build, the length should be the same as your training sword, but the weight should be reduced to about eighty percent the weight of your training sword [therefore between about eleven and fourteen ounces]. If it is either too long or too heavy, it will not be suitable. The center of balance needs to be nearer to the handle, otherwise it will not be easy to use. See photo 43:

–

十八 眼法身法手法步法之實習

EIGHTEEN: HOW TO PRACTICE THE EYE MOVEMENTS, BODY STANDARDS, HAND TECHNIQUES, AND FOOTWORK

眼法者。使眼上下左右前後一瞬卽明。而手中之劍。同時亦到着目的之謂。簡單言之。平時須寧神靜坐。含養目光而已。凡人身眼珠之視物。明與不明。全在瞳神放大。與縮小。及眼珠伸出與縮進。換言之即將視線之焦點。切合於目的物是也。焦點切合。則目的物清晰。焦點不切合。則所視之物。不明晰矣。故學者。須保養精神。使眼珠全部有力。在刹那間。有放大縮小伸張退縮之力。但練習之法。是在逐日工夫。每日于大光之下。行前後左右上下之回顧。顧時目的物。以字為佳。初則其字大而近。繼則字小而遠。務使一看卽明。手中之劍。卽刺所看之物。此法於黑暗中。鬭光中。斜光中。皆宜頻頻行之。每日晨間百次。晚間百次。不可減少與中輟也。

劍法中之眼光。不在久視。而在敏鋭。故常看細小之洋板書。及食蒜韭辛辣烈酒等物。皆宜避之。狂怒與女色。猶為禁忌。

As for the eye movements, the instant your eyes focus on a spot above or below, left or right, forward or back, the sword in your hand at the same time reaches the target. First of all, you must daily calm your spirit with silent meditation to nourish your vision. Seeing clearly or not clearly depends entirely on your pupils expanding or contracting, and on your eyelids opening wide or squinting. To put it another way, it is all a matter of making a focal point down the line of sight resolve upon an object. Bringing the point into focus makes the object clear, whereas if the point is not brought into focus, the object will be indistinct.

You must cultivate spirit so as to fill your eyes with strength and the ability for instant expanding or contracting, opening or squinting. But the practice method is a daily training. Each day, in the full light of day, look around you in front and behind, to the left and right, up and down. When looking at specific things, words are best. Start by looking at large words nearby, then move on to smaller words farther away. [Apparently it would help to fill your practice space with varying sizes of Chinese poetry after all.] Furthermore, as soon as a word comes into focus, the sword in your hand should stab toward it. You should then practice this method also at sunset, at dusk, and in the dark. Do it every morning and evening, a hundred reps each. Neither slacken nor give up.

Eyesight within the sword art is not a matter of looking at anything for a long time, simply seeing it keenly. Avoid excessive reading of tiny print, and the consuming of garlic and spices [i.e. foods that might make the eyes water], and alcohol. Rage and lust are also to be avoided.

手法者。即言全臂運用之法。肩節要卸得下。肘節要變得快。腕節要圓活而有力。此三節。於劍法中為特別重要之煅煉。非如使長槍大戟者。可以忽略也。但此三點之要求。言之甚易。而欲實用如意。非長久之實習煅煉。不能得心應手也。

普通執劍。大半執持甚固。此謂之死把劍。其利。所執之劍不易落。其弊。不能活用。武當劍。執持甚鬆。謂之活把劍。活把劍之利。能活用。但不久練得訣。恐為人擊落。其執法。以大指及三四指執之。其食指與小指。時常鬆開。其掌中似可容物之狀。在擊刺之時。其劍之活用玄妙。非執死把劍者所可比擬。但煅煉方法。頗需時日者也。

練則之勁起於丹田。發於腰脊。由臂而達於劍尖。此謂劍術中之勁路。此層工夫內外皆備。須默度體察而煅煉之。前輩云解得此意。非仙即是道。不得此中意。百煉白到老。

The hand techniques have to do with the movement of the entire arm. Your shoulders should release downward, your elbows should adjust quickly, and your wrists should be loose but strong. It is especially important in the sword art to train all three sections of your arm, not like in the spear or halberd arts, in which they can be mostly ignored. Yet while the importance of the three is easy to discuss, if you want to easily make actual use of them, you will be unable to do so proficiently without training over a long period.

Most will grasp the sword too tightly, a “lifeless grip”. What is good about it is that you will not easily lose your sword, but it has the drawback of making you unable to wield your sword in a lively way. The grip in the Wudang sword art is more relaxed, a “lively grip”, which makes you able to wield your sword in a more lively way, but unless you get the knack of it over a long period of training, it may render your sword easily struck from your hand by an opponent.

This grip uses the thumb, middle, and ring fingers, while the forefinger and little finger remain looser, as though the palm can hold yet a little more. When striking or stabbing, your sword’s profound liveliness will outmatch those using the “lifeless grip”, but the training method will require more time.

During practice, power comes from your elixir field, issues from your lower back, goes through your arm, and reaches the sword tip. In the sword arts, this is called the “power path”. This level of skill needs both internal and external practice, both contemplation and experience in order to develop it. It was said by previous generations: “By understanding this central concept, you will become enlightened to the method. If you do not understand this central concept, you will practice your whole life in vain.”

步法者劍術中達成戰鬭之目的者也。若步法不純。身法手法雖精。仍不能殺敵致果也。步法中要項有三。其一速。其二穩。其三輕。初練時。以兩足之外邊行走。不以全腳掌貼地。因其起落需時。行動不速之故。初習者。其足掌必痛楚。且行走時。極不安穩。但學者。不可因之中輟。凡屬進退斜行側行諸法。每日晨昏務須煅煉一次。日久足邊之皮骨自固。痛楚自無。而行走亦安穩且捷矣。

全足。分胯節膝節掌節。此三節必須煅煉純軟。每日壓膝。凹胯。攀掌。吊腿。諸事。每逢暑期。必須行之。三載以後。其腿自軟。其行走。自輕靈而速捷矣。

The footwork in the sword art is the means by which you attain your objective in a fight. If your footwork is not good, then despite mastery in the body standards and hand techniques, you will remain incapable of defeating the opponent. The footwork must be three things: fast, stable, and light.

In the beginning, step with the outer edges of your feet rather than touching down the whole sole of the foot, which would slow down the lifting and lowering of your steps. You will in the beginning probably get some aching in the soles of your feet and your stepping will not seem very steady, but you must not give up due to these things. Practice in this way advancing, retreating, stepping diagonally, and stepping to the side. You must do a session of this every morning and evening. After a while, the sides of your feet will have tougher skin and bone, the aching will naturally disappear, and your steps will be both steady and swift.

The entire leg divides into the sections of hip, knee, and foot. The three sections must go through flexibility training. Practice these things every day: press your knees. [i.e. With one leg slightly squatting and the other straightened a half step in front of you, press the knee of the straightened leg to loosen the hamstrings.], open your hips [with either a butterfly stretch or a straddle stretch], pull your feet [with both legs outstretched in front of you on the floor or one foot at a time], and lift your legs [either by placing your foot on higher and higher ledges or by performing swinging kicks toward the top of your own head]. Practice these things even more ardently in the summer. After three years of this, your legs will be very flexible and your steps will be agile and quick.

身法者變化進退四法之表現。卽補助手法步法之不足者也。其最要之部。如含胸拔背。如脊梁中正。如活腰轉身。如氣沉丹田。皆稱之曰身法。凡習武術者。無論練拳練劍。非含胸拔背不能變化得勢。如挺胸曲背。則行動必板滯。而無勢矣。其二。非脊梁中正。不能姿勢正確。若脊梁歪斜。則四肢不正。而動作與方向亦不正確矣。其三。非活腰轉身。不能進攻有力。凡人之力。皆出於腰。能用腰者。其力久而旺。不然。以兩臂之力襲人。終不能貫澈目的也。其四。非氣沉丹田。不能久鬭。兩人肉搏之時。其相火已升。若不氣沉丹田。則氣喘痰升。喉必乾。眼必昏。而足亦不穩矣。故此四部。為身法中最要之件。與眼法步法有密切關係。初習武術者每易忽咯。不知劍法中。最重身法。故不憚繁而反復言之。

The body standards are four crucial things expressed during the alternations of advance and retreat, and which compensate for the inadequacies of hand techniques and footwork: contain your chest and pluck up your back, keep your spine erect, keep your waist lively and your torso limber, and sink energy to your elixir field. Collectively these are called the body standards and are to be performed by all who practice martial arts, be it a boxing art or a sword art.

1. If you do not contain your chest and pluck up your back, you will be unable to adapt and gain the upper hand, for if you are sticking out your chest and arching your back, your movements are sure to be stiff and powerless.

2. If your spine is not erect, you will be unable to get your posture to be correct. With your spine askew, your limbs will be misplaced, causing your movements and angles to also be incorrect.

3. If your waist is not lively and your torso is not limber, you will be unable to powerfully attack. The body’s power always comes from the waist. If you are able to use your waist, your strength will last longer and be abundant, but if you instead attack an opponent relying on just the strength of your arms, you will never be able to carry out your objective.

4. If energy does not sink to your elixir field, you will not be able to fight for a long period. When two people fight, their fire will already be rising. If energy does not sink to your elixir field, you will pant until your throat is dry, your vision will blur, and your footing will become unsteady.

These four things are the most essential body standards and are intimately connected to eye movement and footwork. Beginners will tend to easily overlook them, being unaware that within the sword art it is the body standards that are the most weighty consideration, and thus we should not be afraid to reiterate them constantly.

以上所述。眼手步身諸法。為劍術中單行補助法為。學劍者。最為重要之煅煉。學者幸勿忽視可也。

The ways of eye, hand, step, and body are each of them methods of assisting the sword art, and thus they are the most important things in the art to train. Please do not ignore them.

四法歌

SONG OF EYE, HAND, STEP, AND BODY

手到脚不到。自去尋煩惱。

低頭與灣腰。傳授定不高。

腹內深流沉。遇敵如火燒。

眼到脚手到。方算得玄妙。

If your hands arrive without your feet,

you will be taking too much of a risk.

If you lower your head and bend at the waist,

your training has truly not been of a high level.

If energy is sinking deeply within your abdomen,

you will meet the opponent like a burning fire.

When your eyes, feet, and hands arrive in unison,

then you may regard your skill as profound.

–

附錄

APPENDICES

–

李師芳宸傳略

BIO OF LI JINGLIN

李師諱景林。字芳宸又字芳岑。冀南棗強縣人。河北世家也。兄弟五人。伯仲叔皆經商於故里。季早歿。師最少。其祖以技擊聞於兩河間。師幼時得父之傳授。桓桓有俠士風。及壯。遨遊塞外。遇異人皖籍陳世鈞先生。先生沉默寡言。出沒無蹤。冬夏一衲。係武當嫡派。能天盤地盤人盤劍術。師受其業數載。復習太極拳中平槍摔角等技。皆極精勁。時當清季。國勢日替。欲走保定習陸軍。陳先生規之曰。『汝宿根頗厚。且與余有緣。今既習人盤劍。若繼之以地盤天盤各劍術。則吾業可傳。劍俠可成。若棄此而為他業。觀汝功名固不薄。奈何徒勞碌耳。於國仍無補也。汝五年後。稍稍顯達。十年後位至疆圻。十五年後漂流四方。於公於私兩無所成。汝其誌之。二十年後。或與我會於江淮之上乎。』師當時報國心切。竟别陳先生。習陸軍於保定速成學堂。嗣卽執戈躍馬。決勝疆場。曾敗吳子玉於關東。破馮煥章於南口。率塞外健兒十餘萬。出關入關者數次。開牙建纛。彪炳一時師在軍中。常以技擊諸術親授將士。恂恂然如弟兄父子。故所部於戰鬭時。奮勇衝鋒。能以白刃肉搏取勝。在關外時。日本人嘗與比劍。輒敗。請授藝。師允而未行。蓋以日人陰鷙。未易與也。公暇輒教其家人。故其家多能劍術。師有妻妾三人。公子二。長名書剛。業歧黄。次名書真。畢業日本士官學校。女一待字閨中。師於天津督辦任內。與東省總師張雨亭不洽。遂辭去南遊江海間。已復至粵與諸革命先進過從。十六年國民革命軍渡江北伐。蔣總司令夕賴其擘劃。完成統一。師功成不居。回首都組織中央國術館。期吾民族振奮精神。強種救國。歷辦全國國術比試大會。元秀親受其業。退而述成此編呈政。師閲後曰。『汝能記其根略以惠同門。實吾近年所欲成而未竟之志。汝卽付梓可也。』今則誨語如聞。哲人已萎。緬懷風範。不禁高山景行之思。

Li Jingling, called Fangchen, as well as Fangcen, was from an aristocratic family in Zaoqiang county, Hebei. He was the youngest of five brothers, but the fourth of the brothers had died young. All of their uncles were local merchants, but their grandfather had been a martial artist well-known in the area between the two rivers, the Yangtze and Yellow. While Li was young, he was taught by his father, and he had a very heroic prowess.

When he grew up, he did some wandering north of the Great Wall, and there met an unusual man, Chen Shijun of Anhui. Chen was a man of few words. He appeared and disappeared without trace, and he wore the same clothes regardless of winter or summer. An exponent of the Wudang branch, he was skillful in the “sky realm”, “ground realm”, and “human realm” sword arts. Li spent several years learning from him, then also practiced Taiji Boxing, long spear, Shuaijiao, and other skills, and he became very powerful in all of them.

During the last years of the Qing Dynasty, the nation was increasingly in decline. Li wished to go to Baoding and train with the army, but Chen tried to dissuade him: “The purpose you have inherited from your previous life runs deep. You and I are bound together by fate. So far you have only learned the ‘human realm’ sword art. If you keep at it and learn also the ‘ground realm’ and ‘sky realm’ sword arts, then my teachings can be passed down, and you can become a sword hero. If you abandon this work so you can attend to some other, I can see that your skill will earn you a fame that will not be meager. But you will toil in vain, for you will still not have rescued the nation. Five years from now, you will have gradually become a star. But ten years from you, you will be posted to some frontier. Then fifteen years from now, you will be drifting all over the country, having achieved nothing at all, either for others or for yourself. Remember this: twenty years from now, we might bump into each other again on some river.”

However, Li was intent upon serving the nation and ultimately parted ways with Chen and went into the army at the Baoding Accelerated Training School. He then held up his weapon, spurred his horse on, and dominated the battlefield, defeating Wu Ziyu at Guandong and smashing Feng Huanzhang at Nankou. He led over a hundred thousand troops beyond the Great Wall, entering and exiting the passes many times. Bearing his teeth and planting flags, his time in the army was glorious. He often used his martial arts to personally instruct his officers and men, giving them the respect due to brothers, fathers, and sons. For that reason, his troops would charge into battle courageously, and were able to seize victory with swords or fighting hand-to-hand.

While in the northeast, Japanese swordsmen often challenged him, and were always defeated. They asked him to teach them his skill, to which he consented but never made good on because he considered the Japanese to be sneaky and cruel, as well as hard to coexist with.

He spent his spare time teaching members of his own family, and thus most in his family are capable with a sword. He had three wives, two sons. His eldest son, Shugang, is a doctor of medicine, while his second son, Shuzhen, is a graduate of the Japan Noncommissioned Officers School. He had a daughter as well, but she has no husband as yet.

Li served as Marshal of Tianjin, but was at odds with Zhang Yuting, the commander over all eastern provinces. So he resigned and wandered south, followed the Yangtze to the sea, then went on to Guangdong to be with colleagues who had advanced the revolution. Then in 1927, the National Revolutionary Army crossed the Yangtze during the Northern Expedition. Commander-in-Chief Chiang Kai-shek was inclined to rely on Li’s planning and thereby succeeded in unifying the nation.

Without claiming any credit for his services, Li then went to Nanjing and organized the Central Martial Arts Institute. His hope was to inspire our national spirit, to strengthen the masses and save the nation. Therefore he arranged the National Martial Arts Gathering.

I received personal instruction from him. I then wrote it all down into this book and presented it to him for his approval. After reading it through, he told me: “You’ve managed to make a record of the essentials. This will be helpful to your fellow students. Actually, I’ve wanted to do this for years now, but never had the chance. Go ahead and publish it.” I still seem to hear his words of instruction, even though the wise man has since withered away. I cherish the memory of his noble demeanor and I cannot help but miss his lofty integrity.

–

武當山劍術近代系統表

RECENT LINEAGE OF THE WUDANG SWORD ART

陳世鈞先生──李芳宸將軍

Chen Shijun > General Li Jinglin

〔李芳宸將軍〕 ﹛ 施承志 張長義 韓慶堂 李慶瀾

Li Jinglin > Shi Chengzhi, Zhang Changyi, Han Qingtang, Li Qinglan,

郭憲三──山東國術館同人 郭起鳳 楊德山 張長勝 李樹桐 張金榮 張英振 梁振英

Guo Xiansan (colleague at the Shandong Martial Arts Institute), Guo Qifeng, Yang Deshan, Zhang Changsheng, Li Shutong, Zhang Jinrong, Zhang Yingzhen, Liang Zhenying,

鄭炳垣 高守武 黃元秀 金一明 吳心穀 張存周 蔣桂枝──天津國技社同人 劉成虎

Zheng Bingyuan, Gao Shouwu, Huang Yuanxiu, Jin Yiming, Wu Xingu, Zhang Cunzhou, Jiang Guizhi (colleague in the Tianjin Martial Arts Society), Liu Chenghu,

萬籟聲 林志遠 葉大密 曹晏海 張孝田 張孝才 褚桂亭 諶祖安 袁偉 錢西樵

Wan Laisheng, Lin Zhiyuan, Ye Dami, Cao Yanhai, Zhang Xiaotian, Zhang Xiaocai, Chu Guiting, Chen Zu’an, Yuan Wei, Qian Xiqiao,

沈爾喬 章殿卿 郝家俊 高振東 陳微明──至柔拳社同人 趙道新

Shen Erqiao, Zhang Dianqing, Hao Jiajun, Gao Zhendong, Chen Weiming (colleague at the Achieving Softness Boxing Society), Zhan Daoxin,

胡鳳山 孫振岱 朱國禎 朱國祿 蘇景由 郭世銓 馬承志 伍崇仁

Hu Fengshan, Sun Zhendai, Zhu Guozhen, Zhu Guolu, Su Jingyou, Guo Shiquan, Ma Chengzhi, Wu Chongren

〔黃元秀〕 { 陳兆祥 江光華 葉景成 盛鍾泰

Huang Yuanxiu > Chen Zhaoxiang, Jiang Guanghua, Ye Jingcheng, Sheng Zhongtai

〔葉景成〕──楊國治

Ye Jingcheng > Yang Guozhi

〔葉大密〕 { 濮玉(女) 葉季齡 武當拳社同人

Ye Dami > Pu Yu (female), Ye Jiling (colleagues in the Wudang Boxing Society)

〔褚桂亭〕 { 滕南璇 孫仲英 金陵各軍官

Chu Guiting > Teng Nanxuan, Sun Zhongying (army officers in Nanjing)

(附記)李師所傳門人甚多今就所知者開列如上其餘容再版續登

Note:

Li taught a great many students. Presented in this are merely the ones I know of. The others will be listed in a second edition.

–

劍之歷史

SWORD HISTORY

考劍之起原。黃帝時。蚩尤造兵作亂。帝與戰。執而戮之。是時兵器大行。故黃帝本行紀云。『帝採首山之銅鑄劍。以天文古字題銘其上。』又管子地數篇云。『昔葛天廬之山發而出金。蚩尤受而制之。以為劍鎧。』可知劍之創製。發明甚古。拾遺記曰。『顓頊高陽氏有畫影劍騰空劍。若四方有兵。此劍飛赴指其方則克。未用時。在匣中常如龍昑虎嘯。』雖所述劍之效用。頗涉神奇。不足為訓。然畫影騰空二劍。當有所據。非誕言也。及夏之初。禹鑄一劍。藏之會稽山。孔甲曾採牛首。鐵鑄劍。銘曰夾。商之太甲。鑄一劍曰定光。武丁鑄一劍曰照膽。皆有載籍可考。周公定周禮。劍之製法。詳於考工記。昭王自鑄五劍。以投五嶽。名曰鎮嶽尚方劍。穆王時。西戎獻昆吾之劍。切玉如泥。是劍不僅中夏流行。且及於邊裔矣。爰及春秋戰國之世。上自朝廷。下及庶民多佩之。所以尚武也。如季札使北過徐。徐君喜其劍。子路初見孔子。雄冠劍佩。卽其明證。至歐冶干將之徒。以善鑄聞於吳越。太阿龍泉之劍。以破敵稱於荊楚。則劍在當時。不僅習俗好尚。且能威服三軍矣。秦漢之際。始皇作定秦劍以張武功。高祖得赤霄劍而斬蛇起義。光武微時。亦在南陽得一劍曰秀霸。因知劍史深遠。漸成神物。故魏晉以還。乃有魏武於幽谷得一劍。上有金字曰孟德。晉孝武埋一劍於華山頂銘曰神劍。及雷煥見牛斗間有紫氣。而知豐城有寶劍等事。梁武帝命陶弘景造神劍十三口。用金銀銅鐵錫五色合為之。唐貞觀時。魏博將聶鋒有女曰隱娘。少時有老尼授以劍術。既嫁。曾隨節度使劉悟左右。後不知所之。又宋史載關西逸人呂洞賓有劍術。百餘歲而童顏。步履輕疾。頃刻數百里。人以為神仙按洞賓名巖。避黃巢亂。隱居終南後不知所終。劍用既廣。因入技藝。既傳習於女流。復推行於方外。浸假而為小説家言。仗義鋤奸。神奇變化。穿鑿附會。轉失其真。要之。劍亦武器之一。習之所以鍛鍊筋骨。用之可以禦敵防身。則自古迄今如一也。

When we examine for the beginning of swords, it is in the time of the Yellow Emperor, when Chi You built up an army to rebel against him. He battled with the emperor, who then captured him and had him executed. That was the point when weapons began to be in great use. The “Record of the Great Yellow Emperor’s Eastern Travels” says: “The emperor had copper taken from Mt. Shou to be made into a sword, and he had it engraved with astrological text in ancient script.” Guanzi, chapter 77 says: “A mountain in Ge Lu burst and [produced flooding which] brought forth gold. Chi You received it and worked with it to make swords, armor, spears, and halberds.” It is evident from these examples that swordsmithing was invented very early.

It says in the Record of Recollected Lost Works [book 1]: “Master Zhuanxu Gaoyang possessed the swords of Shadowmaker and Skyflyer. If armies came from anywhere, the swords flew up, pointed in their direction, and cut them down. When not in use, they roared in their case like a dragon and a tiger.” Although this scenario is a story of the miraculous and not to be taken seriously, the two swords of that name apparently do exist and are not fantastical.

In the beginning of the Xia Dynasty, Emperor Yu had a sword made and stored it away at Mt. Huiji. King Kongjia had iron taken from Mt. Ox Head and made into a sword with his name engraved on it. King Taijia of the Shang Dynasty had a sword made called Assured Glory. King Wuding had a sword made called Shining Courage. These descriptions can all be examined in books.

The Duke of Zhou finalized the Rites of Zhou, in which the standards for making swords are detailed in the “Record of Artisans”. King Zhao had five swords made and each sent to one of the five sacred mountains. They were all inscribed with “Pressing Down the Mountains To Hoist Up the Way of the King”. In the reign of King Mu, the western barbarians presented him with the Kunwu sword. It cut through jade as though it was but mud. This shows that swords were not only commonly used within China, but also in neighboring territories.

In the Spring & Autumn and Warring States eras, from court officials above to the multitude below, most wore swords, and so there was an esteem at that time for the martial quality. Ji Zha went north to Xu, and there the Prince of Xu admired his sword. When Zilu visited Confucius for the first time, he had an impressive cap on his head and a sword at his waist. Both of these examples demonstrate this common esteem.

Then there was the expertise of Ou Ye and Gan Jiang at casting swords, well-known in the kingdoms of Wu and Yue, and the successful battlefield use of the swords Tai’E and Dragon Well, praised in Jingchu. Swords in those days were therefore not only a customary display of martial respect, they were also able to intimidate armies. In the dynasties of Qin and Han, the First Qin Emperor had a sword made called Establishing Qin to display his martial prowess, the Han emperor Gaozu obtained the sword called Red Clouds and slew the white serpent with it, starting the revolt that would lead to the ousting of the Qin Dynasty, and before the emperor Guangwu was in power, he obtained from Mt. E in the Nanyang region a sword called Elegant Overlord.

Because sword history goes back do far, the sword has gradually become something supernatural. During the Wei-Jin period, Emperor Wu of Wei [Cao Cao] obtained from a secluded valley a sword on which was already written in gold his style name of “Mengde”. The Jin emperor Xiaowu had a sword buried at the summit of Mt. Hua that was engraved with “Magic Sword”. Lei Huan noticed a strange energy up in the sky between the constellations of Ox and Ladle, and thereby understood there was a precious sword below in Fengcheng. The Liang emperor Wu commanded Tao Hongjing to make thirteen magic swords using all five metals – gold, silver, copper, iron, tin – combined.

In the Tang Dynasty, Zhenyuan era, General Nie Feng of Weibo had a daughter who would later be known as the Nie the Hermit Woman. When she was a girl, there was an old nun who taught her the sword art. She later got married, then entered the service of the governor Liu Wu, then [after saving his life with magic, she] disappeared [to live up to her name].